AI: Learning challenges and artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence in your homeschool

by Kathy Kuhl

While speaking at the MASSHope homeschool convention, I promised to write about artificial intelligence. Today I’ll post some initial definitions and thoughts.

What is AI?

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a technology that enables computers and other machines to mimic human intelligence. It appears to learn, comprehend, solve problems, create, and make simple decisions. Think of AI as autocorrect on steroids, deducing a lot about language by analyzing word sequences rather than an actual intelligence.

But some are more optimistic. IBM says:

Applications and devices equipped with AI can see and identify objects. They can understand and respond to human language. They can learn from new information and experience. They can make detailed recommendations to users and experts. They can act independently, replacing the need for human intelligence or intervention (a classic example being a self-driving car).*

I’d say that’s unduly optimistic. AI can mimic humans making recommendations, and some may be good. But there are problem with AI.

To train an AI to generate language, developers use a Large Language Model (LLM). The program processes a massive amount of data to create its foundation model: trillions or quadrillions of bytes off the internet. It collects data, then quizzes itself on guessing the next word, as described in a recent Wall Street Journal article. (Link below.)

What does AI lack?

1. AI lacks a wise teacher

AI is not educated by a wise and ethical teacher. Instead, imagine a child with perfect memory, listening to and remembering everything millions of people say, taking it all in like a vacuum cleaner. That will include errors and lies and sources of dubious value.

That’s why AI developers are concerned about data poisoning—people deliberately sharing inaccurate data in order to corrupt the information or add misinformation. It’s a reasonable fear.

2. AI has no common sense

“AI doesn’t know what it doesn’t know,” to quote my favorite person and computer scientist, Dr. Frederick Kuhl. For instance, he explained, AI doesn’t know that water runs downhill. (So don’t ask it to plan your irrigation system as of this writing.)

It also has no judgment. No mother ever taught it not to lie. It only mimics and can mimic unwisely.

It generates responses that tend to be overly optimistic. A classical example is its response to a goofy business proposal, like selling junk door-to-door.

Artificial intelligence even has an uneven track record on summarizing. On my phone, I’ve seen it summarize my emails, sometimes giving me the complete opposite of the clear meaning of the sender. So I don’t trust its summaries. But it can save you time by generating one, if you study the results skeptically and carefully.

Because of these serious flaws, I was horrified when I read that some parents are asking AI to generate homeschool curriculum. I won’t do that more than I’d ask AI to design an airplane for my child to fly in.

So is AI good for anything in our homeschools?

Yes, in limited ways. Here’s a few I’ve seen so far.

1. Artificial intelligence is useful for spellcheck and grammar check. But we want our students to verify, because AI may apply the wrong rule or the wrong spelling. We’ve all seen auto-correct go awry.

2. Also, it can be a helpful research tool. But it’s what Dr. Kuhl calls “an enthusiastic, overconfident assistant.” So be wary. Verify.

When I use AI for research, I like the Perplexity app, which includes links to its sources. Then I check them.

3. You can ask AI to draft specific tasks you can later edit and think through carefully.

Most importantly, don’t use AI for tasks that exercise skills you need to keep fresh. Don’t let your student use it for tasks he or she has not mastered, or skills that they need to keep fresh.

In April 2025, a technology reporter for the Wall Street Journal wrote how relying on AI cost him hard-earned skills. While living in Paris, Sam Schechner once used AI to help him draft a careful email in French to his son’s soccer coach. It was quick, accurate, and convenient. So Schechner began to use it more often. But before long, he realized his written French was getting rusty.**

In his article, Schechner spoke with experts:

“The question is what skills do we think are important and what skills do we want to relinquish to our tools,” said Hamsa Bastani, a professor at the Wharton School and an author of that study on the effects of Al on high-school math students. Bastani told me she uses Al to code, but makes sure to check its work and does some of her own coding too. “It’s like forcing yourself to take the stairs instead of taking the elevator.”**

Similarly, another professor wrote that he used AI to summarize latest research in his field. But he knew he was missing details that his brain (but not AI) might use to gain other insights.

Dr. Kuhl pointed out that when AI becomes good enough to be incorporated into software we don’t call it AI. Word prediction software, speech-to-text and text-to-speech–which are all helpful tools for our struggling learners– are some examples. So is translation software. I use it to write a friend who doesn’t speak English, but I check it cautiously, or use it to verify my poor translations.

What skills do we want our children to learn and practice?

What tasks should our students not delegate?

- Learning correct grammar and spelling

- Summarizing

- Synthesizing information

- Reading with discernment

- Choosing sources wisely, verifying data from multiple sources.

- Writing clearly.

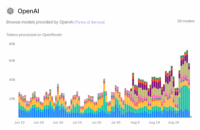

I could go on about how AI is changing higher education, based on the frustrations of professors I know. But for now, just this teaser. Here’s a graph generated by OpenAI (yes, I appreciate the irony) showing ChatGPT usage increasing as school began. **

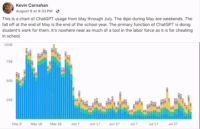

And here, courtesy Kevin Carnahan’s Facebook post, is a screenshot of what happened during summer vacation. He explains that the dips during the school year are weekends. Then, it’s “No more teachers, no more books, no more essays that AI cooks.” ***

Conclusion, or the beginning?

So when we begin to have our students use AI, we need to set limits and goals for its use. Technology always comes with risks and benefits.

More importantly, we need to consider the purpose of education. What are your goals in teaching your child?

What questions do you have about AI and your child who learns differently?

For additional reading:

- John West, “I”ve Seen How AI ‘Thinks.’ I wish everyone could.” The Wall Street Journal, downloaded October 13, 2025.

- Sam Schechner. “How I Realized AI Was Making Me Stupid – and What I Do Now: Backers of the new tech say it will free us to be creative, but studies show that avoiding mental effort can cause your brain to atrophy.” Wall Street Journal, downloaded April 3, 2025.

- Grace Snell, “ChatGPA: AI is forcing teacher and students to redefine education.” World Magazine. Posted July 17, 2025, downloaded September 6, 2025.

Other sources

*IBM definition of artificial intelligence

**AI use rising as academic year begins: OpenAI’s graph of tokens processed on OpenRouter June 10-August 29, 2025. Downloaded 9/6/25.

Ken Carnahan’s screenshot of the same graph for May 8-July 27, 2025, showing use drops over summer vacation. Downloaded from Facebook 9/6/25.